Hebrew Parsing: Use the Consonants, Luke!

Doing things the hard way…

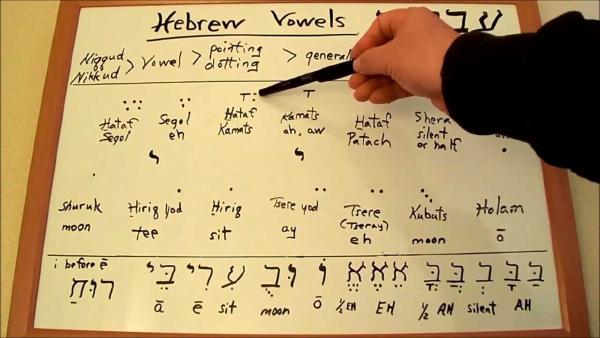

After a semester of Hebrew, and being almost through the first-year textbook, I suspect that I’ve been doing some things an unnecessarily difficult way. I’ve been trying to memorise paradigm tables, including the diverse and erratic permutations of all the vowels. But anyone who has studied Hebrew in any depth knows that vowels hold an interesting position in the language. The text of the OT was originally written using only the consonants. The vowel markings were added much later by the Masoretes (allegedly somewhere between 500-1000AD). This has led to some historic disputes among protestants about whether the vowel points should be considered a part of the “inspired” text. I recently stumbled across a site called withoutvowels.org which contends that only the consonantal text is truly a part of the inspired Tanakh.

I’m certainly not going to try and settle that debate here, but instead I want to suggest a practical theory that flows out of such historical knowledge. Native speakers of modern Hebrew (and Arabic) get by just fine without any vowels. Apparently ancient Hebrew scribes didn’t feel they would be depriving future generations of anything critical by recording the OT using only consonants. So the question is, were the ancient Hebrew scribes able to live without the vowels only because they knew the vowels by heart from their oral tradition? Or is it possible that they felt the consonantal text itself contained enough grammatical detail that vowels were genuinely unnecessary?

Few if any natural languages have no ambiguities at all. In Greek there are words like οτι that can function either to indicate content (“he told them that he would go soon”), or as giving causation (“he spoke to them because he would go soon”). But does a Greek speaker consciously distinguish between these two meanings as he reads Greek? Or in his mind, is the word just “οτι”, and he understands which meaning it has intuitively (even subconsciously) from context? Similarly in English, we write the adjective “close” (I am close to you) and the verb “close” (please close the door) in exactly the same way. Native speakers pronounce these words with an extremely subtle distinction. They pronounce the verb with a slightly harder S-sound at the end, more like “z” than “s”. But they never seem to complain that an extra letter is needed when writing the word to prevent confusion. They just deal with it.

What I am suggesting is this: perhaps Hebrew was written without vowels because the consonantal text already provides almost everything you need for effective parsing. Am I saying the vowels are entirely grammatically superfluous? No, not at all. That website above provides a (surprisingly helpful) Hebrew grammar tutorial based solely on consonants. But even that site admits (for example) that the Piel and Pual stems have no consonantal differences in form. From the perspective of a purely-consonantal grammar, Piel and Pual are one and the same thing, with only context to tell you which meaning should be understood. This is problematic because there is a noteworthy difference in meaning between them (Piel indicates an active-voice verb, while Pual indicates passive-voice). Once you supply vowels, then there is a difference in form between them. That means that wherever context does not provide a conclusive answer, the oral-vocalic tradition is our only source (other than sheer speculation) for deciding when these verbs should be understood as passive. But perhaps the ancient Hebrew scribes were comfortable with this? Maybe they regarded this difference the way we think about “close” and “close”. Perhaps they would have felt that it was rare for anything more than context to be required for a reader to understand whether a verb should be Pual instead of Piel? It’s a possibility worth considering.

How does this cash out for us as non-native Hebrew students, trying to work out how to read the Hebrew OT? I suggest that while we should be grateful for the distinctions encoded for us by the meticulous addition of the niqqud (vowel points, etc) by the Masoretes, we shouldn’t make our lives any harder than they need to be. We should recognise that vowels in Hebrew are a lot more volatile and changeable than consonants. It’s good that we know how the Masoretic tradition pronounced their words, but we don’t have to let the intricacies of their pronunciation grammar determine how we learn parsing. This is a consonantal language, so if we want to understand it, perhaps we should focus on the consonants! Let me show you an example of what I mean.

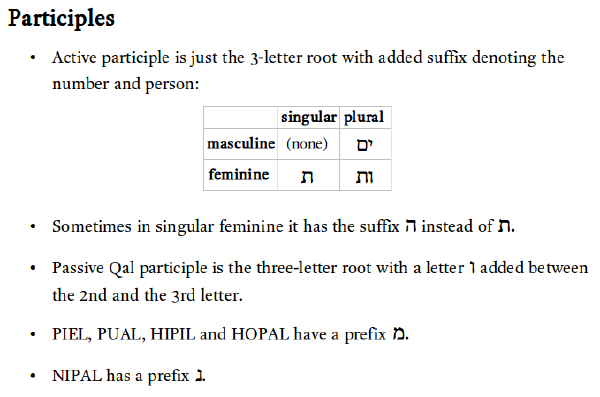

The Participle Paradigm from EBH5

This is the full paradigm for participles in the major stems from Elementary Biblical Hebrew 5th Edition by Athas and Young:

Can you imagine trying to memorise every different configuration of all those little vowel dots under the letters? Can you imagine having to try and write them out during a test? I can! Believe me, having to write out a bunch of these without missing a vowel, an accent or a dagesh is not easy.

The Participle Paradigm from WithoutVowels

Synthesising from a couple of separate pages, let’s have a look at the purely-consonantal paradigm for participles from withoutvowels.org:

MUCH simpler, right? I’d have a much better shot at memorising that. However, it has a flaw. How do you tell the difference between Piel and Pual? … You can’t. The consonantal forms are exactly the same.

A Hybrid Approach: Vowels as Last Resort

I propose a hybrid approach to parsing. What if we began by trying to parse these participle forms as best as we could from the consonants alone? How far would we get? It turns out, we would get a surprisingly long way by just learning a few simple rules. Consider this flow-chart:

-

Does it have a prefix-mem?

- Yes: Hithpael, piel, pual, hiphil or hophal

-

Does it have a prefix he+taw (hith)?

- Yes: Hithpael

- No: Piel, Pual, Hiphil or Hophal

-

Does it have a prefix he?

- Yes: Hiphil or Hophal

-

Does it have a yod between the 2nd and 3rd root consonants?

- Yes: Hiphil

- No: Hophal or reduced Hiphil

-

Is there an O-class vowel under the prefix consonant?

- Yes: Hophal

- No: Hiphil

-

Is there an O-class vowel under the prefix consonant?

-

Does it have a yod between the 2nd and 3rd root consonants?

- No: Piel or Pual

-

Is there an O-class vowel under the 1st root consonant?

- Yes: Pual

- No: Piel

-

Is there an O-class vowel under the 1st root consonant?

- Yes: Hiphil or Hophal

-

Does it have a prefix he?

-

Does it have a prefix he+taw (hith)?

- No: Qal or Niphal

-

Does it have a prefix nun?

- Yes: Niphal

- No: Qal

-

Does it have a waw between the 2nd and 3rd root consonants?

- Yes: Qal passive

- No: Qal active

-

Does it have a waw between the 2nd and 3rd root consonants?

-

Does it have a prefix nun?

- Yes: Hithpael, piel, pual, hiphil or hophal

As you can see, those six purely-consonantal questions (highlighted with dark blue text) give you enough information to decide which type of participle you are dealing with in the large majority of cases. The only remaining ambiguities are between Piel vs Pual and reduced-Hiphil vs Hophal. Interestingly, you can resolve both of these ambiguities by asking pretty much the same simple question about the vowels: is there an O-class vowel where the stem-name implies there should be? The forms of this question are in light blue text.

Do you understand what we’ve just done? With only a few yes-or-no questions, we’ve just managed to recognise all the major participle stems without having to know any of the detailed vowel patterns. We had to know to look for the O-class vowel to spot a couple of passive forms, but we didn’t even need the specific vowel, just it’s class. We didn’t need to know any rules-of-shewa, any vowel-reduction patterns or why in the world a hireq, sere and seghol might morph into each other. None of that was actually required to understand the meaning of the word. You might need to know the vowel patterns for your next Hebrew test, but you don’t necessarily need to know them in order to read your Hebrew Bible.

Some Closing Thoughts

In closing, I want to make it clear that I’m not trying to be at all critical of the textbook by Athas and Young. They’ve done a great job, and I’d be lost without that book. To their credit, they’ve done the hard yards of scholarship to integrate all the research that has been done on the meaning of Hebrew vowels. I’m playing in a sand pit, while Athas and Young are building skyscrapers! What I am trying to do is figure out the best way to conceptualise Hebrew grammar for the purpose of reading it quickly and smoothly. By trying to prioritise the consonants in my own mental parsing process, my hope is to read it more and more the way a native speaker/reader would, with more instant recognition and less vertical zig-zagging of the eyes.

I’m also not sure yet how far this consonants-first principle will take me. Will it fundamentally break down when applied to other paradigms, like finite verbs or nouns? That remains to be seen. I’m optimistic about the possibility, since Hebrew was written for so long with no vowels at all, but I’ve got a lot left to learn!